Freedmen’s Town’s history is buried deep in its roots

Written by Karina Hollingsworth on February 24, 2022

By: Karina Hollingsworth

Houston, TX— Southwest of Downtown Houston is a close-knit region brimming with African-American heritage.

No, the community is not filled with tall statues or mile-long monuments. Instead, the neighborhood has other artifacts like the African American Library at the Gregory School.

The library’s building was previously a school for African American children, which opened in Houston in 1926.

Just two blocks south of the library, on the junction of Wilson and Andrew St., lies a lane that at first glance resembles a red brick road. However, to the people of Freedmen’s Town, those crimson bricks represent their forefathers’ rivers of blood and sorrow, the same blood that flows through their veins.

These are just two of the reasons why Zion Escobar, executive director of the Houston Freedmen’s Town Conservancy, works relentlessly to preserve the legacy of Freedmen’s Town.

“Part of why Freedmen’s Town is so deeply personal for me is because I’m trying to understand a part of my history and my heritage that I don’t have the answers for right now,” Escobar said. “Like many Houstonians, the diaspora has gone and flourished, but you don’t really know the story about your roots. Freedmen’s Town is that answer to that question for a lot of people.”

Escobar emanates ‘Black Girl Magic,’ from her crown of coiled locks to her knee-high boots.

It was apparent from the scuffs on her boots that she had traversed the streets of Freedmen’s Town many times. Walking around her forefathers’ streets with grace, confidence and pride was a joy for her.

“This is black excellence,” Escobar said with a girlish smile.

While Escobar was practically skipping along Wilson St., she heard the hammering of a hammer and the drilling of a drill. A home with boarded windows and a wide-open entrance attracted her eye.

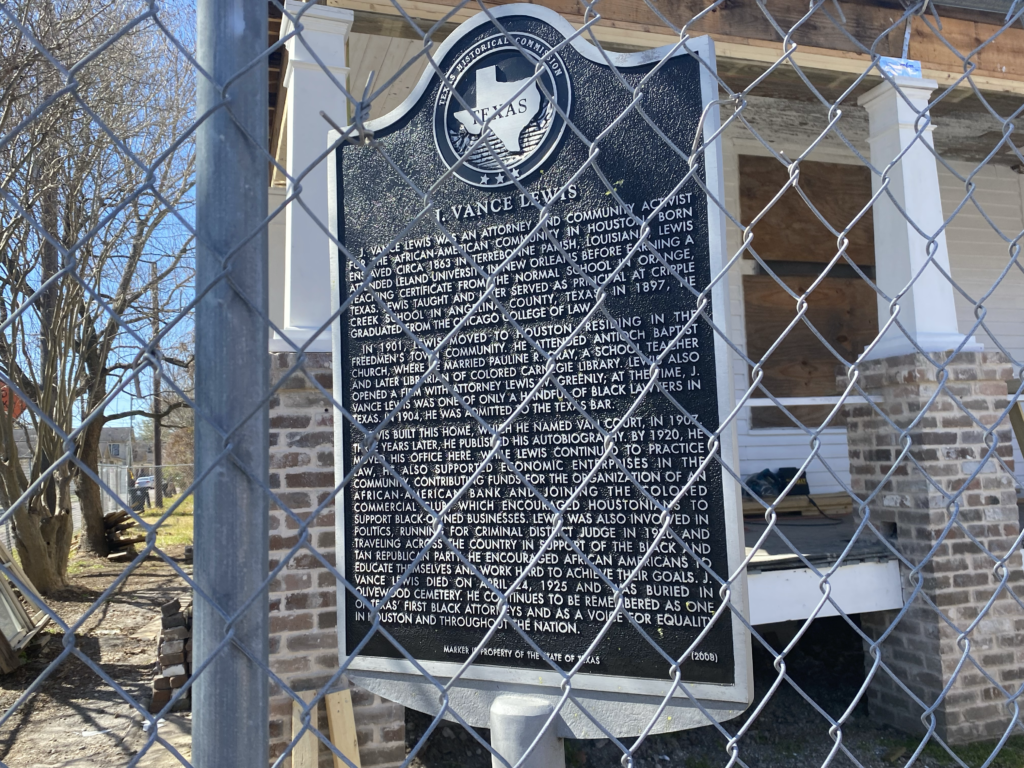

Construction workers were busy restoring the home that had captured her attention. “We’re just restoring this house that belonged to a lawyer back in the 1900s,” the construction worker said.

“That’s Joseph Vance Lewis’ house,” Escobar whispered. “He was the first Black lawyer in Houston. Back in the day, African Americans couldn’t go to a regular court of law. But, here at Van Court, right outside of Vance Lewis’ home, African Americans could have their case heard.”

Escobar continued to roam the streets of Freedmen’s Town, where community members routinely hailed her. Finally, she came to a halt and smiled at everyone.

Dr. Elmo Johnson contacted Escobar as a community leader and pastor of Rose of Sharon Missionary Baptist Church; he expressed thanks for her hard work and understanding of Freedmen’s Town.

Dr. Johnson proposed a visit to The Founders Memorial Cemetery, just across the street from his church, and Escobar gladly agreed.

Once in the cemetery, Dr. Johnson scurried around freely, announcing multiple facts about the Founders in their final resting place.

“This is David Porter Richardson, the private secretary of Sam Houston,” Dr. Johnson said. “Here lies James Collinsworth, born in Tennessee, drowned in 1806 in Galveston.”

Even though each headstone had a short inscription, Dr. Johnson was well-versed in the history of each Founder. Dr. Johnson’s eyes narrowed onto an object in the rear of the cemetery in mid-sentence. He abruptly came to a halt and pointed.

“That right there is a hanging tree,” Dr. Johnson said. “Whenever you have limbs that come out, that’s easy to throw a rope around and tie it up that’s a hanging tree. They did us like that, unfortunately, and that saddens me. There were other trees, but Hurricane Harvey killed those. Still, this one remains.”

Previously, Freedmen’s Town served as a haven for formerly enslaved individuals and their descendants seeking to flee bigotry and persecution.

Today, citizens like Dr. Johnson prefer to remain in Freedmen’s Town to help preserve its heritage.

The Houston Freedmen’s Town Conservancy aims to begin relocating former inhabitants of Freedmen’s Town. Additionally, they are attempting to acquire and rehabilitate a property set for destruction.

“We are wanting to keep this home as it is, protect it, double down on it, make sure it looks as historic as it is,” Escobar said. “We want to make sure it’s functional, and it’s a healthy place. Hopefully for a family that used to live in Freedmen’s Town that was displaced.”

Public donations to assist with maintaining this house at 1609 Saulnier in the Freedmen’s Town neighborhood may be made at alliesoffreedmenstown.com.

About the author