Black Cowboy Museum showcases treasured history

Written by admin on February 27, 2021

By Serbino Sandifer-Walker Texas Southern University

Deep in the heart of the Texas town of Rosenberg, there’s a cowboy named Larry Callies who has turned his passion and reverence for Texas history into a life-long mission; a mission to educate the world about Black cowboys through a museum he founded in 2017.

Tucked almost unnoticeably off Third Street in a strip center, the Black Cowboy Museum has two six-feet storefront windows protecting a treasure trove of unsung cowboy history behind them.

:strip_exif(true):strip_icc(true):no_upscale(true):quality(65)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/gmg/QBZFQVXA45AHNMW3ULYQU7TZAA.jpeg)

“This is the only Black Cowboy Museum in the world,” said Callies, whose voice cracks with pride as he describes the museum he started after he “stepped out in faith.”

Callies, who stands a lean 5′10 in Tecovas cowboy boots, once had a promising singing career, opened for Selena and performed for late President George H.W. Bush. He was represented by the same manager as legendary country singer George Strait.

However, his singing career was cut short when he developed a voice disorder called vocal dysphonia, a condition that damages the vocal box or larynx.

He had to undergo Botox therapy for 27 years just to be able to talk. Now, he speaks with a tight-strained cracking pitch, but can no longer sing.

“When I lost my voice, I lost my manager and I lost my band,” Callies said. “But, I’m a Christian first and a cowboy second. I know that when God takes one thing away, he gives you something else.”

Callies, who retired from the U.S. Post Office after 34 years, knew that “something else” was his Black Cowboy Museum.

“I was going through some bad times and God just said, it’s time to open up your Black Cowboy Museum,” Callies said.

The cowboy life is in Callies’ blood. His grandfather, father, uncle and cousin were all accomplished cowboys.

They called his father, Leon Callies “Puggy” and they called him “Little Puggy.” His father put him on a horse when he was 3-years-old. He taught him how to be a good horseman and calf-roper while working for one of the biggest cattle ranchers in Texas in Wharton County. He was raised in Boling, Texas and became a championship cowboy. He graduated from Boling High School in 1971 and attended Wharton Junior College.

His father learned how to be a championship cowboy from his brother Big Preacher Williams, who back in the 40s, 50s and 60s was known as the best cowboy in the country, said Callies.

Williams’ son, Tex, would go on to win several state rodeo championships starting in 1967 while in high school when the rodeos first desegregated. Callies won a state championship in 1971. All of that cowboy history is spread out in photos, artifacts and more in the three-room museum.

The cowboy historian wanted to set the record straight about the Black cowboy.

He said Hollywood glamorized the cowboy with characters portrayed by actors like John Wayne and essentially erased the Black cowboy from the scene.

He explained that he traced the word cowboy back to England in the 1700s and Texas in the 1820s.

“In Texas, they had a house boy, a yard boy and someone who worked the cows was called a cowboy,” Callies said. “You couldn’t call a white man a cowboy. He would want to fight you.”https://965be2fb18172770e684d38e9825a390.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-37/html/container.html

Callies further explained that the Black men were called the cowboys because they were slaves.

“The white man would say, ‘I’m not your boy. I’m a cowhand or a cowman or a cowpuncher,’” Callies said.

Since opening the Museum, people from all over the world have reached out to him wanting to learn more about the Black cowboys, he said.

“The Black cowboys were the heroes of this country. They fed this country,” Callies said.

Callies is also an expert saddle repairman, a skill he perfected while working at the historic George Ranch in Richmond. He has had several cowboys bring their saddles to the museum.

He wants to expand the Black Cowboy Museum to a larger location. He said the Black cowboy history is too important to be forgotten.

■ This story was written to chronicle Houston’s Black history as part of a partnership between KTSU2, “The Voice”, and KPRC-TV, for Black History Month.

___________________________________________________________________________

About the author

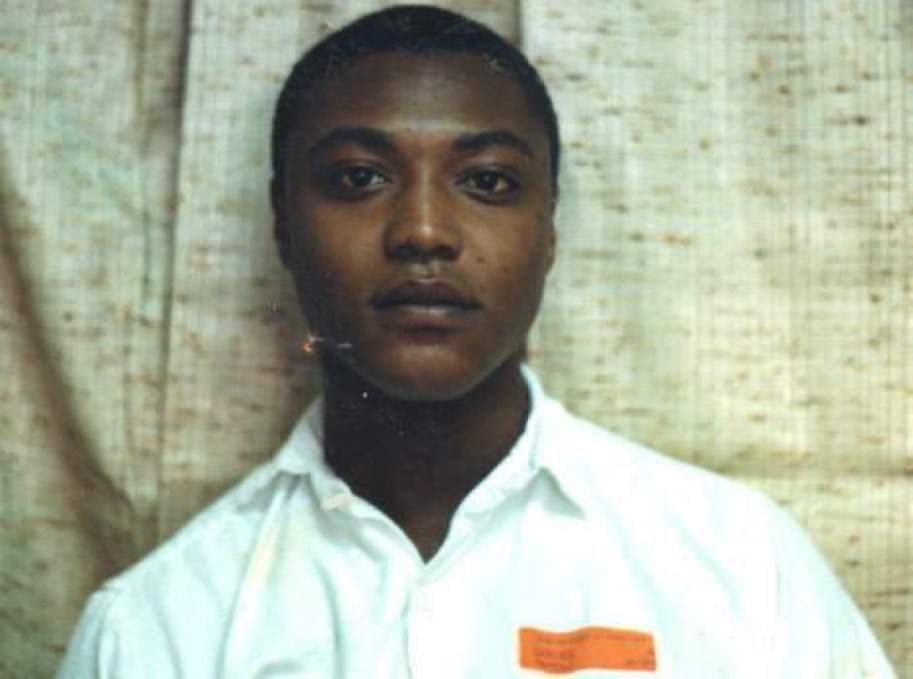

:strip_exif(true):strip_icc(true):no_upscale(true):quality(65)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/gmg/MYO3GUMY25HTDHXU2FNGDKC5YA.jpg)

Serbino Sandifer-Walker is a journalist and Texas Southern University journalism professor.